Applying systems, futures and design thinking in strategy and practice

Part 2 of the Integrated Approaches to Thinking series

Across health and human service sectors, practitioners working in strategy, policy and service design often face environments defined by complexity and constant change, where evolving needs and entrenched inequities cannot be solved by simple or linear solutions. Traditional approaches to improving societal outcomes often miss the nuance, interconnections and lived experiences at the heart of these challenges.

In my previous article, I wrote about how integrating systems, futures, and design thinking can help to plan for solutions that are adaptive, inclusive and resilient. This second article explores how this integration works in practice and highlights tools, crossovers and considerations for implementation.

How thinking lenses shape what we see

Each thinking lens offers a different perspective on complexity:

Systems thinking helps reveal interconnections, feedback loops and structures that shape outcomes.

Futures thinking stretches our view to explore possibilities, anticipate change and prepare for uncertainty.

Design thinking focuses on lived experience, iterative problem-solving and testing solutions in real-world contexts.

Used together, these lenses provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of complex challenges and help organisations and teams to plan strategically, design solutions that meet needs and adapt as circumstances evolve.

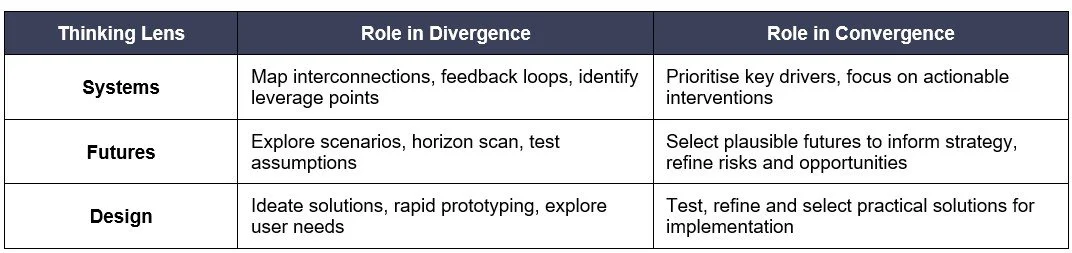

Start with framing

Before picking up a tool, it’s essential to decide: Do we want to open up our thinking or narrow down? in order to understand the problem better . Inevitably, you will want to do both in order to embrace adaptive learning. Integration is guided by knowing when to diverge and when to converge (Table 1). This framing helps us decide which tools to use and for what purpose.

Divergence expands perspective, surfaces possibilities and resists rushing to solutions. It asks the questions ‘what might be happening here?’ and ‘what else could we consider?’

Convergence narrows our focus, makes trade-offs explicit and moves from exploration to decision. It asks the questions ‘What matters most?’ and ‘which options are feasible in order to act now?’

Table 1: Divergence and convergence in integrated thinking

Looking inside the toolbox

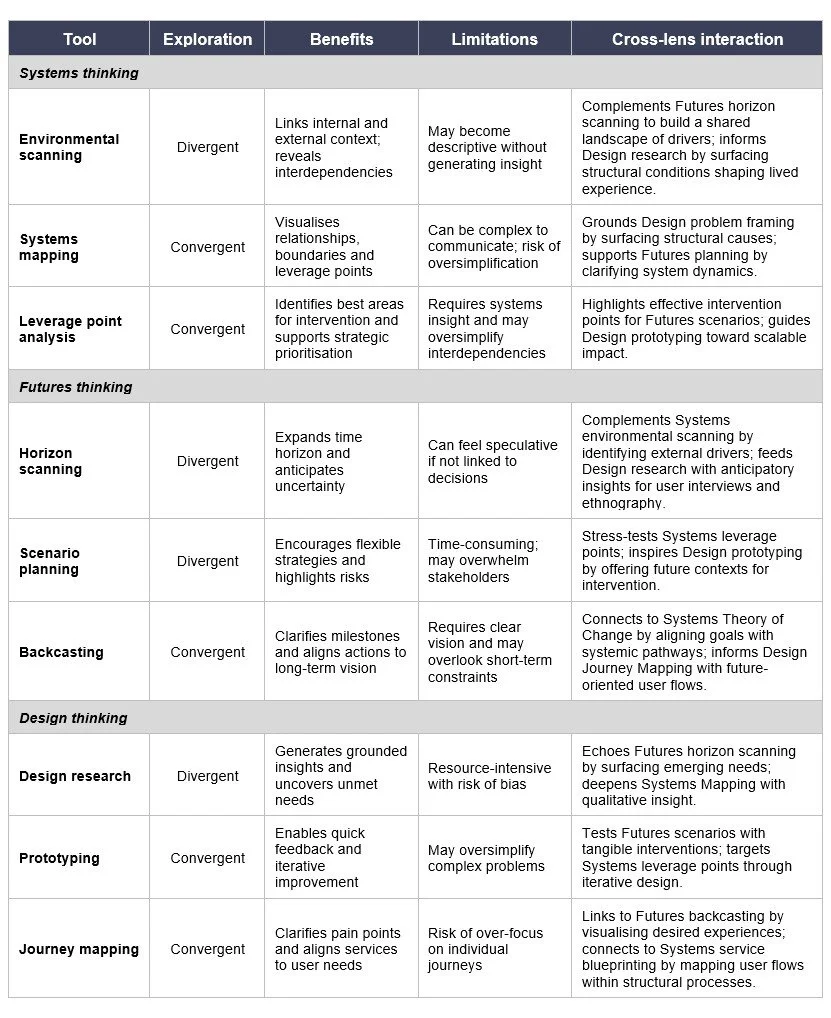

When working in complex environments, whether in practice or policy, practitioners rarely rely on a single lens. Instead, they move between systems thinking to understand structural dynamics, futures thinking to anticipate change and design thinking to include lived experience. Each approach offers distinct tools, but the real value lies in how these tools interact.

The table below outlines nine commonly used tools across these three lenses. It shows how each tool explores complexity (divergent or convergent), what benefits it brings, where its limitations lie and how it connects with tools from other thinking approaches. These crossover points are where integration happens. This isn’t a definitive list, but a practical toolbox to help choose, combine and sequence tools in ways that are strategically aligned.

Table 2: Integrated thinking toolbox

So what? Hopefully by mapping how tools diverge, converge and intersect, it surfaces new ways to understand complexity and act with intention. Integration isn’t about using every tool, it’s about choosing combinations that unlock insights, stretch thinking and embed lived experience in planning, design and impact.

Now what? Whether shaping policy, designing programs or facilitating cross-sector collaboration, intentional consideration of which tools best suits the context and how blending lenses might deepen impact is a worthwhile journey. Start with one lens, then layer another and stay open to iteration. Integration is mindset before method, and one that invites learning above all to strengthen adaptive public health strategy over time.

A working example

A state-level initiative is tasked with improving access to healthy food in communities experiencing higher levels of disadvantage. Traditional approaches focus on individual behaviour change, nutritional education or retail mapping. While useful, these methods often overlook the systemic drivers of food access and the lived realities of those navigating constrained environments.

An integrated thinking approach reframes the challenge:

Systems thinking maps structural and policy-level drivers such as zoning regulations, transport infrastructure, retail density and rising costs in living. Tools like causal loop diagrams reveal how limited access reinforces poor nutrition, which in turn affects health outcomes and deepens inequity. This insight informs design problem framing and supports futures scenario testing by identifying leverage points and feedback loops.

Futures thinking stretches the horizon to explore scenarios such as climate-driven supply disruptions, shifts in food culture and emerging models like mobile markets or urban agriculture. Horizon scanning surfaces signals of change like circular food systems or platform-based delivery models, while scenario planning helps test how these futures might reshape access, demand and policy levers. These insights connect to systems leverage points and feed design research by offering future contexts for prototyping.

Design thinking brings in community voice through empathy interviews, journey mapping and co-design. These methods uncover invisible barriers such as cultural disconnects, stigma around food assistance or logistical challenges. They test assumptions and biases and prototype potential solutions with users. This lived experience deepens systems mapping and validates futures signals by testing emerging needs and service models.

The result is a food environment strategy that integrates structural insight, anticipatory vision and community voice, producing solutions that are more equitable, resilient and responsive to change.

From thinking to practice

Systems, futures, and design thinking each offer distinct ways to navigate complexity. By intentionally combining these lenses, we can design strategies that are not only responsive to current challenges but also adapt to future conditions and ensure lived experience and expertise is included. This isn’t about making sure all approaches are used, it’s about learning to move between them, using the interplay between them to surface better questions, test assumptions and co-create solutions that matter and are designed for impact.